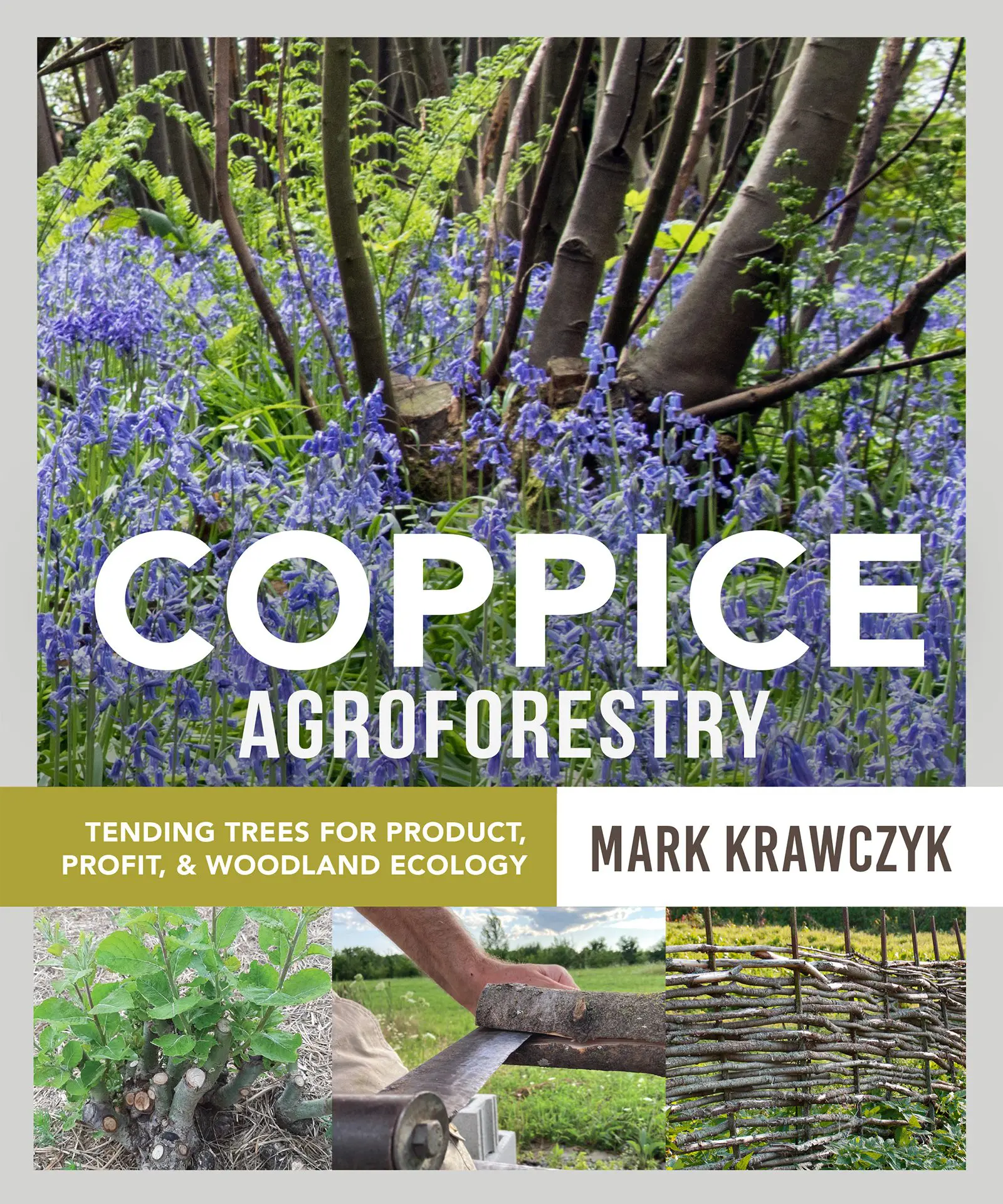

In his book, Coppice Agroforestry, Mark Krawczyk looks at the ancient practice of coppicing, blending it with modern science, systems thinking, and tools to ground it firmly in the 21st Century. So, whether you have a few trees or an entire forest, this book is the must-have practical guide for homesteaders, farmers, foresters, land managers, and educators who ally themselves with the remarkable resilience of woody plants. Today, we share an excerpt from the book that explains what coppice is.

Introduction: What is Coppice?

The lives of humans and woody plants have been inextricably linked for as long as our species has populated the planet. Even in modern times, when we are so dramatically dissociated from the resources and landscapes that support us, it’s remarkably enlightening to reflect on all the ways trees influence our lives and our experience of the world around us.

Trees provide…

- Shelter

- Building materials

- Shade

- Fuel: for heating, cooking, electricity

- Industrial production

- Transportation

- Food: for humans, livestock, mammals, birds, insects, fungi, and microbes

- Craft materials

- Erosion control

- Climate stabilization

- Water cycling

- Wildlife habitat

- Medicine

- Enclosures

- Soil building processes and biomass

- Air filtration

- Beauty and inspiration

It’s hard to imagine life on Earth without the myriad benefits proffered by trees. In fact, life as we know it would not be possible without them.

Keeping all this in mind, take a moment to reflect on your relationship (and more broadly, our cultural relations) with the forests that support us. For the vast majority of us in the one-third or “developed” world, that relationship is virtually unconscious. Most of us have no idea where the wood that shelters us, keeps us warm, cleans and oxygenates our air, and stabilizes our soil actually comes from, and even more importantly, how it’s produced and managed. Historically, only a privileged few were affluent enough to detach themselves from their relationship with woodlands for anything other than hunting and recreation. Industrial culture has enabled this disconnect to become the norm, but today our need to reconnect with our woodlands grows ever clearer.

Coppice forestry is an ancient silvicultural practice that provides one of the best living examples of a symbiotic, cooperative relationship between humans and forest ecosystems. While the modern ecoforestry movement also places humans as active and beneficial participants in the landscape, the longevity of coppice woodlands, stools, and pollards the world over pay testament to the widespread suitability of this land management technique. As we’ll explore in later chapters, when well-managed and maintained, coppice woodlands and their biological community are exceedingly healthy, robust, and resilient, host a broad diversity of species, age classes, and forms, and yield an array of forest products for human use.

This book attempts to reconnect our culture with the woodlands that we are part of. While our focus rests primarily on coppice woodland management and other related means of symbiotic silviculture, a much deeper theme underlies the nuts and bolts of system design, establishment, and maintenance. Our real goal is to help initiate and inspire the revival of a woodland lifestyle—a life lived in direct and complementary relationship with the forests that nurture us. This is no small task, but I believe that to bring about the change we wish to see in the world, we first need to envision what it looks like. So please accept this invitation to reconnect, restore, and reinhabit our true home in a way that benefits all beings.

What is it?

The term “coppice,” both a noun and verb, comes from the Old French word copeiz, which today translates to couper, meaning “to cut.” Additional sources connect the word to the Greek kolaphos, “blow,” via the Latin verb colpare, “to cut with a blow.” While etymology can be enlightening, it doesn’t offer much in the way of insight into the practice itself.

Coppice management is an ancient silvicultural technology where broad-leaved woody plants are cut on cycles of 1 to over 40 years during dormancy and allowed to regenerate from the stump. These stump sprouts develop into a new crop of poles harvested during the next felling cycle.

This vegetative regeneration or “stump sprouting” is a common ecological process often found along roadsides and utility lines, where regular clearing by road crews and utility companies establishes “coincidental coppice.” Often, for many people, this incredible expression of biological vigor is a nuisance. We were trying to clear the land after all. But only in a culture flooded with cheap energy can we afford to view an abundant self-renewing resource as waste. Yet when we recognize the immense potential of the humble stump sprout, we can develop production systems that are largely self-maintaining, which is the essence of coppice agroforestry.

Dissecting Our Definition

The ability to form a permanent structural stem with perennating organs (buds) well above the ground differentiates most woody plants from their herbaceous kin. This adaptation affords woody plants the opportunity to shade out herbaceous competition, avoid many herbivores (especially the big ones), and occupy a vertical niche that extends potentially hundreds of feet skyward. Broadly speaking, the term “woody plants” refers to plants with rigid stems high in compounds called lignin and cellulose. However, plants may be called “woody” even if they don’t make actual wood. In this book the term “woody” will refer to tissues made of, or plants that make, actual wood in the strict sense: the secondary xylem lying beneath the bark of a tree or shrub, the hard fibrous material forming the main substance of the trunk or branches of shrubs and trees, composed primarily of lignin and cellulose.

Generally speaking, most broad-leaved woody plants (angiosperms)—trees and shrubs that have wide leaves as opposed to needles and bear their seeds in fruits instead of cones—will coppice, meaning they respond to cutting during dormancy with vigorous resprouting come spring. Some of the best-known examples include maple, ash, oak, linden, hazel, willow, and poplar. The vast majority of broadleaved woody plants are deciduous, meaning they lose their leaves during the dormant season. Conversely, “evergreens” retain their foliage throughout the year. These trees are typically conifers, which bear cones containing seeds and have needle-like leaves. Most conifers do not coppice in the true sense of the word, although parallel forms of management that we discuss later do allow us to leverage resprouting in conifers.

Under coppice management, woody plants are cut on cycles of 1 to 40 or more years. Traditional felling cycles—the frequency of harvest—revolved around the desired size of materials for a particular product and the species being managed. Poles harvested for fence posts 3 to 6 inches (7.5 to 15 cm) in diameter require a longer cycle than shoots used for 1-to-2-inch (2.5 to 5 cm) diameter thatching spars or pea sticks. We generally consider coppice stands harvested on 1-to-5- year cycles “short-rotation” and those exceeding 5 years “long-rotation.”

The timing of felling operations is critical to the health and vigor of shoot regrowth. While many species will still resprout after cutting during spring and summer, historically, coppicing was carried out during the winter months once trees had gone dormant. Winter felling is desirable for several reasons. During dormancy, trees experience considerably less stress, and insect, fungal, and bacterial populations are quite low, reducing the likelihood of disease and infection. Also, first-year shoots from a freshly felled stool (the stump of a coppiced tree that’s managed for resprouts) are tender and pithy and benefit from a long growing season to harden off before the arrival of autumnal frosts that can damage or kill young sprouts.

Traditional winter felling and extraction work, especially on frozen ground, dramatically reduces the overall impact on understory vegetation and soil structure while improving extraction routes. The heavy work of tree felling and extraction is well-suited to the cold temperatures of winter, while craft and value-added work was typically performed in spring and summer, creating a varied and seasonally balanced livelihood.

Many coppice sprouts emerge from preventitious (dormant) buds embedded beneath the bark, capable of prolific new growth following disturbance. Often these buds develop in the spring at the base of a recently felled tree. We call this remnant stump a coppice stool. This contrasts with the suckering tendency of some species, where shoots or suckers emerge from a tree’s root system. Cherry, aspen, beech, and black locust (Prunus spp., Populus spp., Fagus grandifolia, and Robinia pseudoacacia) are examples of species prone to suckering following disturbance. While the new shoots emerge from a different portion of the tree, we’ll discuss both stump-sprouting and suckering species throughout this book. And then of course, there’s pollarding—a training system for woody plants that manages sprouts high up on the stem in the crown where they’re out of reach of livestock and wildlife—hedgelaying, and shredding. All of these techniques add diversity to our continuum of resprout silvicultural practices.

So, with a basic understanding of what coppicing is, let’s now look at why it emerged historically as a widespread silvicultural practice that has benefitted human cultures and how it can best be adapted to meet our needs today.